Click to read the story.

NORTHEAST

1. Toddlers

Tom Jones Lean-to, Harriman State Park, NY

Take a deep breath, mom and dad. Actually, don’t. You won’t need it on this easy, 1-mile out-and-back along a quiet footpath to an even quieter backcountry hideaway. Between the gurgling brooks and unending birdsong, there’s enough to hold Junior’s attention while you stroll beneath a canopy of mixed hard- and softwoods.

Link the Victory and Ramapo-Dunderberg Trails .5 mile to the Tom Jones lean-to (first-come, first-serve). For more solitude, pitch your tent in the grassy area above the shelter.

Trailhead Victory (41.230311, -74.140031) Permit None Season May to October

2. Little Kids

Franconia Falls, Pemigewasset Wilderness, NH

The only problem with this trip is that it might spoil backpacking for your kid when he learns that not every trip ends in a 20-foot water slide. That’s a shame because you’ll probably never see your tyke hightail it to camp faster.

Take the flat, 3-mile Lincoln Woods Trail to the first-come, first-serve Franconia Brook Campsites (there are 20), which are a quarter mile below the natural water park. Set up, then it’s off to take your pick of pools, falls, and chutes in Franconia Brook.

Trailhead Lincoln Woods (44.063666, -71.587971) Permit None Season May to October

3. Big Kids

Chimney Pond, Baxter State Park, ME

Calling all mini mountaineers: This trip promises a taste of the heady stuff, without all the commitment. Basecamp at an alpine lake in an amphitheater of Maine’s tallest peaks, then let your kid choose what to do, be it summiting any of the parapets around you (Katahdin is just a 1.3-mile, class 3 scramble via the Cathedral Trail), trying to withstand the icy water, or crawling through the Pamola Caves (.7 mile east of camp).

Climb the Chimney Pond Trail 3.3 miles, ascending 1,400 feet, to the nine lean-tos ($21/night; reserve in advance).

Trailhead Roaring Brook (45.919666, -68.857353) Permit None Season June to October

SOUTHEAST

1. Toddlers

Little Manatee River, Little Manatee River State Park, FL

Step up your I Spy game on this flat, 6.5-mile loop that all but guarantees glimpses of softshell turtles, red-bellied and pileated woodpeckers, alligators, and manatees. Take the Florida Trail 2.5 miles through alternating woods and marshlands to camp in a grove of oak and longleaf pine ($5/person; reservation required).

Trailhead Florida (27.675295, -82.348846) Permit None Season Year-round

2. Little Kids

Ocracoke Island, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, NC

Try selling your kiddo on the maritime woods, dunes, and salt marshes that overlook the Pamlico Sound on the .8-mile Hammock Hills Trail, but keep this tidbit in your back pocket for emergency use: The nefarious Blackbeard sailed these waters.

Pitch a tent at the quiet National Park campground across the street ($28/night), and save this next piece of the story for when you’re roasting s’mores: Local legend claims that you can still see the pirate’s head bobbing in the surf.

Trailhead Hammock Hills (35.125481, -75.923832) Ferry Free Permit None Season Year-round

3. Big Kids

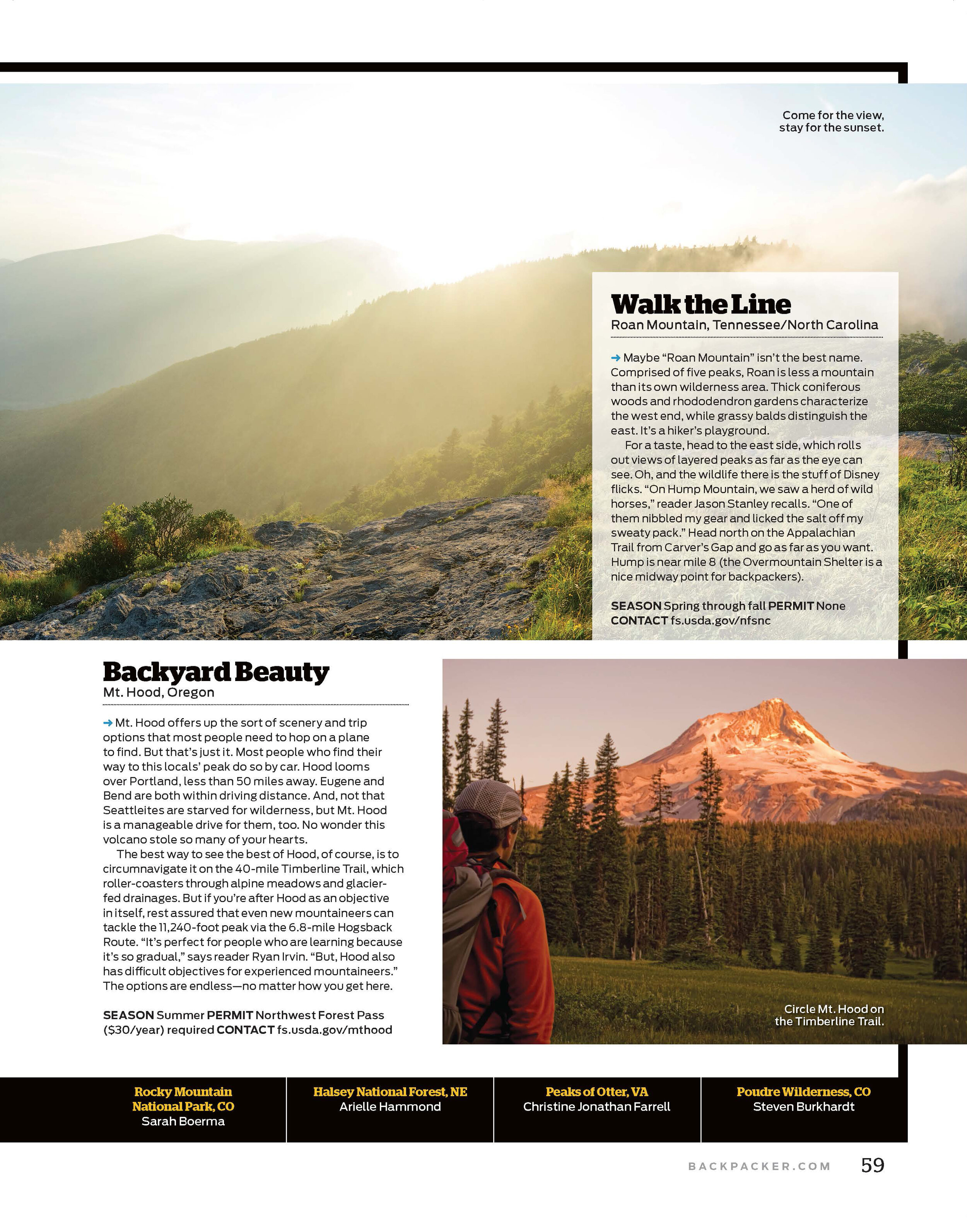

Overmountain Shelter, Pisgah National Forest, TN/NC

Who knows? This could be the trip that turns your little one into an end-to-end thru-hiker. Hop on the Appalachian Trail off US 19 in Tennessee and roller-coaster over Hump and Little Hump Mountains, grassy balds with big views across the Roan Highlands, to Yellow Mountain Gap near mile 4.5. From there, a quick jaunt south (into a new state!) lands you at a giant, two-story barn that sleeps 30 (first-come, first-serve). The ensuing game of manhunt proposes to be ridiculously fun, especially if your kid can convince the other thru-hikers to join in. And we bet mom and dad won’t mind the vista south down the Roaring Creek Valley from the bedroom window.

Trailhead Appalachian US 19E (36.177421, -82.011800) Permit None Season April to November

MIDWEST

1. Toddlers

Au Sable Point Light, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, MI

Mom and dad get history, while Junior gets a shipwreck, enough to keep all parties smiling. Take the mellow former Coast Guard road 1.5 miles across the bluffy promenade overlooking Lake Superior to the wooded Au Sable East campsites ($20; reservation required) with views down to the shore. On the return, follow the beach 1.5 miles back to complete the loop.

From camp, visit the Au Sable lighthouse next-door or venture to the 1918 Gale Staples shipwreck, which pokes out of the sand. Older tots may want to climb on the exposed wooden beams, while the younger ones may simply work at excavating them.

Trailhead Hurricane River (46.665616, -86.166941) Permit None Season May to October

2. Little Kids

Paluxy River, Dinosaur Valley State Park, TX

Kid wisdom: Dinosaurs make everything better. Long-necked Sauroposeidon and T.Rex-like Acrocanthosaurus used to roam through this area, stomping through the rocky area beneath today’s Paluxy River and leaving massive, 3-foot-long prints that fossilized into the limestone.

Set out on a 7.5-mile overnight scavenger hunt on the Cedar Brake Outer Loop Trail. Scan for tracks within the first mile (and wherever you cross the riverbed thereafter). Camp on the wooded ridge overlooking the brown water near mile 3 (reserve in advance) before dropping back down to the river for more sleuthing.

Trailhead Cedar Brake (32.249494, -97.812395) Permit None Season October to June

3. Big Kids

Big Plateau, Theodore Roosevelt National Park, ND

Be honest: You pretend like you’re taking the kids to see bison as a favor to them, but, really, you want to see the 2,000-pound behemoths just as bad. A herd of some 300 of the massive animals grazes year-round on the aptly named Big Plateau, so make it the centerpiece of a 14-mile loop into Teddy’s country.

Day one, walk 8 miles through petrified forests (where kids can examine entire trees turned to stone) to camp on the plateau overlooking the maze of ragged, dusty-brown badlands. Next day, follow the plateau 6 miles to close the loop.

Trailhead Petrified Forest (46.995944, -103.604819) Permit Required (free) Season April to October

MOUNTAIN WEST

1. Toddlers

North Twin Lakes, Medicine Bow National Forest, WY

You could throw a dart at a map of the Snowy Range and end up with a quiet alpine lake that’s less than a few miles from the nearest trailhead and totally vacant. That’s good news for any backpacker, but particularly those carrying a kid.

A good bet: Take the Sheep Lake Trail, which “climbs” 200 or so feet in 1.5 miles to the North Twin Lakes. Like it here? Throw down. Still feeling squirrelly? Keep going. There are dozens of named and unnamed pools on either side of the trail, which wraps north around the Snowies and stays above 10,000 feet. And don’t forget your rod; the fishing here is renowned.

Trailhead Brooklyn Lake Permit None Season May to October

2. Little Kids

Mohawk Lake, Arapaho National Forest, CO

Mini prospectors, mini trainiacs, and mini hikers are in luck, because this 2.6-mile out-and-back has it all. (Plus a seldom-used alternative trailhead that knocks off a mile each way. Score!) You and your brood can duck into abandoned logging cabins and tiptoe along the tracks of an old ore trolley en route to twin Mohawk and Lower Mohawk Lakes.

The trick is to start midway up the Spruce Creek Trail (instead of the popular trailhead down lower off CO 9). From there, link up with the Mohawk Lakes Trail and take it to camp on the west side of Mohawk, the higher of the two tarns.

Trailhead Mohawk Lake (39.421531, -106.074023) Permit None Season June to September

3. Big Kids

The Beaten Path, Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, MT

Got children who want to hike like adults? There may be no better introduction to life-list trekking than the 26-mile Beaten Path. It’s got everything you want from your own bucket-listers (mainly never-ending Northern Rockies scenery), and there’s no right way to do it. So let your kid plan it out because big mountains, lakes, waterfalls, and even wildlife are guaranteed, no matter where she deems worthy of pit-stopping.

Do it southbound, and encourage nights at Rainbow Lake (mile 8) if fishing is on the docket and Skull Lake (mile 17.8) for its primo meadow campsites.

Trailhead East Rosebud (45.193024, -109.640937) Permit None Season June to October

NORTHWEST

1. Toddlers

Oregon Dunes, Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, OR

Most people will flock to the Olympic Peninsula in search of easy-access beach hikes. Let them. New parents should venture south to the quieter Oregon coast, where the 2-mile Tahkenitch Dunes Trail leads through stands of conifer and shore pine to prime seaside real estate.

Set up your tent above the high-tide line near where the Tahkenitch Creek spills into the Pacific and enjoy surfy solitude. The sand alone is plenty entertaining for the youngest tykes, and older ones can climb driftwood beams or explore starfish-filled tide pools.

Trailhead Tahkenitch Creek (43.812965, -124.154343) Permit None Season May to October

2. Little Kids

Sawtooth Berry Fields, Indian Heaven Wilderness, WA

This hike is berry cool, we promise. (And yes, you can use our dad jokes with your kids.) Less than a mile into this overnight adventure into the Sawtooth Berry Fields, huckleberry bushes ripe for picking in summertime begin to line the trail. Let your kids fill up for a midhike snack, and be sure to harvest enough for dessert and pancakes the following morning (each person may haul a gallon per day).

Keep going 6 miles on the Cultus Creek and Pacific Crest Trails to camp at Blue Lake, where you can cast a line for trout to complete a DIY meal.

Trailhead Cultus Creek (46.047665, -121.755311) Permit None Season May to October

3. Big Kids

Four Lakes Loop, Trinity Alps Wilderness, CA

With nonstop swimming for the kids and nonstop vistas for the adults, this 17-mile lake-to-lake epic has only two challenges: 1) deciding how long to basecamp in Siligo Meadows and 2) determining when to summit 8,162-foot Siligo Peak, which will make you look like a hero when the kids realize the views-to-effort ratio.

Take the Long Canyon Trail 6 miles to Siligo Meadows, which nestles beneath folds of granite. From there, check off the 5-mile loop connecting Deer, Summit, Diamond, and Luella Lakes, summiting Siligo en route.

Trailhead Long Canyon (40.923136, -122.812622) Permit Required (free) Season June to October

SOUTHWEST

1. Toddlers

Dunefield, White Sands National Monument, NM

It makes sense, right? White Sands is literally a 275-square-mile sandbox. Nab a permit for one of the 10 backcountry sites, then walk a mile into the dunefield to set up for the night (pack in water). Your tot will enjoy scooting in the white gypsum sand, while you probably won’t mind the view of the 8,000-foot San Andres Mountains.

Trailhead Backcountry Camping Loop (32.810069, -106.264234) Permit Required ($3/person) Season March to November

2. Little Kids

Weaver’s Needle, Superstition Wilderness, AZ

For the past century, people have combed the Superstitions for the Lost Dutchman’s Gold Mine, and all have come up empty—meaning it’s still out there for your little one to find. Some folks say the fortune is buried in the shadow of 4,553-foot Weaver’s Needle, so go there on a 6-mile out-and-back treasure hunt.

Hike north on the Peralta Canyon Trail (#102), cresting the Fremont Saddle near mile 2.5. From there, follow the social path northeast to camp below the Needle, and keep your eyes peeled for the glitter of gold.

Trailhead Peralta (33.397540, -111.348077) Permit None Season October to June

3. Big Kids

Little Death Hollow, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, UT

Whether you’re looking for entry-level canyoneering for your kid or yourself, this will do the trick. Despite its name, Little Death Hollow is neither technical nor scary: It’s 7 miles of typically dry, sinuous sandstone adorned with easy-to-spy petroglyphs. In spots, it’s so narrow that you can touch both walls at the same time.

Tackle it on an 18-mile loop: Descend into its belly and follow the slot on day one. Pop into Horse Canyon near mile 8.5, and find a campsite in a cottonwood grove a mile north. Next morning, turn east into the next canyon and follow Wolverine Creek back to the road, just a half mile north from your car.

Trailhead Little Death Hollow (37.784024, -111.180372) Permit Required (free); self-register at the trailhead Season Year-round; don’t go if rain is in the forecast.